Courage In The Impossible: Gaza’s Poets Speak

Amidst Gaza’s turmoil, poets’ voices resonate. Explore Palestinian poetry’s power and resilience.

Since the start of the ongoing Mahsa Amini Protests, which began in Iran in September 2022 after the murder of Jina Mahsa Amini at the hands of the Morality Police for not wearing her veil properly in public, we’ve heard the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom” travel around the world. In Persian this is “zan, zendegî, âzâdî” (زن, زندگی, آزادی), but the slogan originates in the Kurdish language and the Kurdish struggle for autonomy.

The fight for women’s rights has long been intertwined with the Kurdish independence movement. The Kurdistan Free Women’s Union was established in 1995, and in the same year the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK), which had been co-founded in 1978 by a woman, Sakine Cansız, decided to promote the establishment of more independent female political, cultural, and economic organizations. These establishments were part of broader trends in Kurdish society and the liberalization of Kurdish views on women’s roles. Abdullah Öcalan, also a co-founder of the PKK, theorized that the subjugation of women is the root of all other types of oppression and that society cannot exist in freedom unless women are free.

In 1998, on International Women’s Day, the “Ideology of Women’s Liberation” was presented (possibly by Öcalan, though this is disputed) as a list of principles for women to follow in their emancipation battle. It stated that women had to break free not only from old social roles and the attitude that supported them, but also from total autonomy and self-organization. The Kurmanji Kurdish slogan “jîn, jîyan, azadî” started to become popular just a few years later. Its exact origins remain obscure, but it appeared after the arrest of Öcalan and the Kurdish independence leaders’ decisions to prioritize women’s rights as part of their movement.

In 2012, after the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War, Syrian Kurds established an autonomous government that platformed, among other planks, women’s liberation. The Syrian Women’s Protection Units engaged in combat against ISIS, while women’s civilian organizations continued to address patriarchal attitudes. As more territory was liberated from ISIS control, women from various non-Kurdish communities joined in the movement. They not only participated in the Autonomous Administration’s women’s institutions but also established their own organizations to cater to their specific needs. This bringing together of women across ethnic and religious lines showcased the universalist potential of the Kurdish women’s movement.

It is the history of this Kurdish women’s resistance tradition that has led Iranian Kurdish women to play a leading role in the ongoing Iranian protest movement, which was sparked by the murder of Jina Mahsa Amini, herself a Kurdish woman, but fueled by the desire to demonstrate against the Iranian regime. The slogan “jîn, jîyan, azadî” soon became the rallying cry of these protests, a reference to Amini’s Kurdish origins, and Persian speakers quickly picked it up, translating it to “zan, zendegî, âzâdî.” Although other slogans started circulating, “zan, zendegî, âzâdî” became the most popular one, thanks to social media and the efforts of the Iranian youth in spreading it outside Iranian and Kurdish borders. A notable example is the song “Barâye…” (برای”, “for”) by Shervin Hajipour, composed of various tweets explaining why people were protesting, or the anthem “Sorôde Zan” (“سرود زن”, “Women’s Hymn”) written by Mehdi Yarrahi. Both of these songwriters have since been arrested and sentenced to prison.

This slogan has now been translated into many languages, as people worldwide have shown solidarity for the cause and begun protesting against the current Iranian government. According to the scholar Handan Çağlayan, “the slogan is attractive for its spelling and rhythm and significant for its connotations.” Jîn and jîyan are two closely related words, but jîn in this case should not signify a glorification of womanhood; rather it means “claiming and supporting womanhood as a valuable identity independent of manhood.” Jîyan symbolizes the right to life, and azadî, the right to freedom, “symbolizing the mutuality between womanhood and Kurdishness in women’s political participation.”

To learn more about Kurdish culture, check out our article on deq, the art of Kurdish tattooing. Better yet, consider studying Kurdish with NaTakallam! You can learn either Kurmanji or Sorani Kurdish from native speakers, and the first lesson is FREE, so why not try it out?

Reimagine your language journey with NaTakallam.

Try a session in Arabic, Armenian, English, French, Kurdish, Persian or Spanish.

Languages open doors and minds. Discover new worlds.

Learn Arabic, Armenian, English, French, Kurdish, Persian or Spanish.

Deep dive into a language, packed with culture. Personalized to you.

Choose from Arabic, Armenian, English, French, Kurdish, Persian or Spanish.

Deep dive into a language, packed with culture. Personalized to you.

Choose from Arabic, Armenian, English, French, Kurdish, Persian or Spanish.

You might also LiKe

Amidst Gaza’s turmoil, poets’ voices resonate. Explore Palestinian poetry’s power and resilience.

A smattering of French slang from around the world! Learn more expressions like this with NaTakallam’s native speaking tutors.

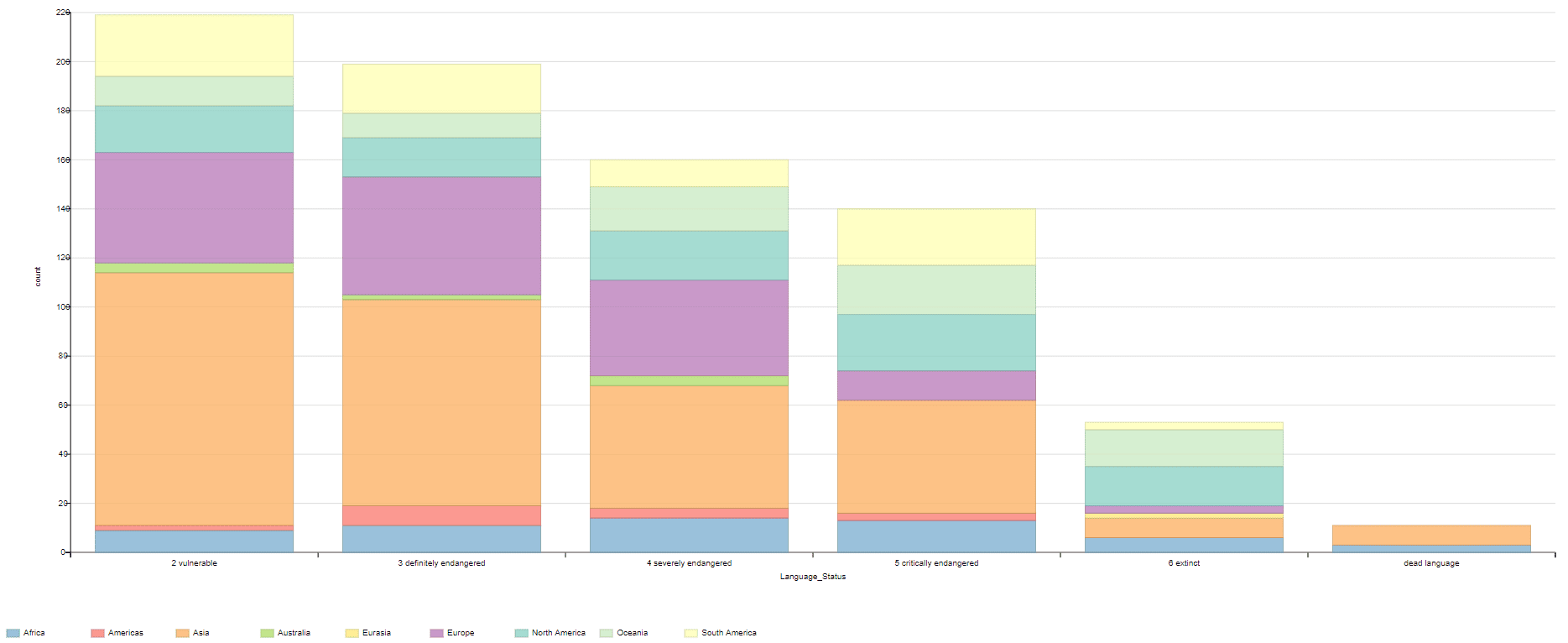

Each language serves as a unique expression of culture, identity and heritage. However, the numbers of speakers of some languages are declining. These endangered languages are at risk of disappearing forever, taking with them centuries of cultural wisdom, knowledge and tradition. Happily, we now have a better understanding of how and why this happens and what we can do to prevent it.

Spanish is one of the fastest growing foreign languages in the world. Get access to the Spanish business world with our native tutors – tailored to your needs.

Improve your proficiency in Farsi or Dari & contextualize your learning with cultural insights from our native tutors. Language & culture go hand-in-hand at NaTakallam.

Looking to do business with Kurdish businesses? Learn with NaTakallam’s native speakers & reach new language (& business) goals – tailored to your professional needs.

Gain an edge with contextualized French learning by native tutors from displaced backgrounds. Flexible, with cultural & business insights, tailored to your needs.

Choose from Eastern Armenian or Western Armenian. Get quality teaching & unique insights from native tutors. Gain an edge with Armenian language skills.

Offer your team a smoother integration or transition with our customized English lessons delivered by bilingual tutors with extensive English instruction experience.

Choose from Modern Standard Arabic or any of our 7+ dialects offered by native tutors across the region. Take your proficiency to the next level & connect with the Arab business world.