Language: A Critical Tool to Unlock Peace and Understanding

Learning a new language can be daunting.

The inevitable mistakes – mispronunciations, misunderstandings – can be embarrassing, but they signify a step toward deeper connection.

When I lived in Lebanon and was new to Arabic, every conversation felt harder than it needed to be. I often mispronounced words or got lost when the dialogue moved beyond the few phrases I knew. Yet, something beautiful emerged. An older man who ran a nearby umbrella stand would often strike up a conversation. Despite moments of misunderstanding, we both made an effort. I spoke Arabic; he replied in English. Every day, we sat together over coffee and practiced each other’s language.

These daily conversations didn’t just improve my Arabic—they created a connection that went beyond words. Each mistake, each shared laugh, was a step toward mutual understanding. This simple exchange revealed a deeper truth: language is not just about communication. It’s a bridge that connects people, cultures, and perspectives, allowing us to break down barriers and foster empathy. And in the larger context of global peacebuilding, these connections become even more vital.

The Role of Language in Peacebuilding

Language is how we communicate; how we share our thoughts, ideas, and feelings. In peacebuilding, clear communication is key to resolving conflicts. The United Nations has long recognized this, as in their 1999 ‘Declaration and Programme for Action on a Culture of Peace’ which affirms peace “not only is the absence of conflict, but also requires a positive, dynamic participatory process where dialogue is encouraged and conflicts are solved in a spirit of mutual understanding and cooperation.”

This idea expanded in the 2015 HIPPO Report, which highlights the needs for strategic communication to build trust in peacebuilding and peacekeeping. It’s about more than just communication; it’s about understanding the other side – literally and figuratively.

Learning to speak someone else’s language is an act of empathy and shows a willingness to connect with “the other,” which is the essence of peacebuilding.

In conflict resolution, this can be incredibly powerful. Take international diplomacy as an example. Multilingual diplomats often have a greater capacity to negotiate and build relationships across divisions because they can communicate in the native languages of their counterparts.

For example, Nelson Mandela’s knowledge of Afrikaans, the language of the ruling white minority during apartheid in South Africa, helped him engage with the Afrikaner community. His ability to speak Afrikaans (in addition to his mother tongue Xhosa and English) enabled him to establish a rapport with those who were initially resistant to his leadership. Mandela’s linguistic versatility helped bridge the deep racial divide in South Africa. His approach showed the importance of language in reconciliation and peacebuilding.

When we learn another language, we are not just memorizing vocabulary or grammar rules, we are gaining insight into their worldview, culture, and experiences.

"If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart."

– Nelson Mandela Tweet

When we learn another language, we are not just memorizing vocabulary or grammar rules, we are gaining insight into their worldview, culture, and experiences.

Breaking Down Barriers With Dialogue

Language learning is about more than just words or clear communication—it’s deeply connected to culture, identity, and perspective, all of which are embedded in the structure of language itself. By learning a language, we gain insights into these elements, which fosters peacebuilding, mutual understanding, respect, and an appreciation for diverse ways of thinking and seeing the world. Thoughtful communication can heal, acknowledge suffering, and affirm dignity.

Dialogue facilitated in a shared language or through translation helps to break down barriers of misunderstanding. By bridging language gaps, multilingualism helps break down barriers that can lead to exclusion or miscommunication, ensuring that everyone’s voice is heard and reducing the risk of misunderstandings that could escalate into conflict.

At the grassroots level, language exchange initiatives have become tools of reconciliation. NaTakallam connects displaced persons with language learners across the globe, showcasing how language can foster mutual understanding. When people from different backgrounds and countries engage in conversation, they humanize each other. This simple act of learning and sharing creates bonds that can dissolve stereotypes and build a culture of peace and justice, one word at a time.

Partnering with NaTakallam is not only an investment in language education but also in global peacebuilding. By providing platforms for displaced persons to share their knowledge and stories, these programs foster cultural exchange, empathy, and the kind of mutual respect that is essential for building a more peaceful world.

Language as a Bridge Through Education

Educating individuals in multiple languages contributes to long-term peacebuilding, and NaTakallam’s programs are a testament to that. By connecting students to conflict-affected individuals, NaTakallam integrates language learning with refugee experiences, fostering meaningful dialogue across borders that promotes understanding and collaboration.

As one Arabic student from the University of Georgia noted after participating in a NaTakallam program:

For so long I thought there was a huge difference between us and them...I wonder what would have happened if I had gone on with the same ideas. Would I have lived my life hating other people? Would I have built up so much hatred that I would have retaliated or attacked one of these groups? If people would just sit down and talk, they would realize how misled they've been. Speaking with and getting to know my Language Partner has been an absolute privilege.

– NaTakallam Arabic Student Tweet

Bridging Divides and Fostering Global Understanding

Language is more than just a tool for communication – it’s a powerful medium for peacebuilding. Whether through simple language exchanges in the street, like my daily conversations at the umbrella stand in Lebanon, or through multilingual diplomacy at the highest levels, language opens the door to understanding, empathy, and reconciliation.

In a world of growing divisions, organisations like NaTakallam remind us that fostering human connection through language can help break down barriers. By learning to communicate across cultures, we create spaces for mutual respect and deeper understanding. Together, we can build a more empathetic, inclusive world where every person’s skills and stories are valued.

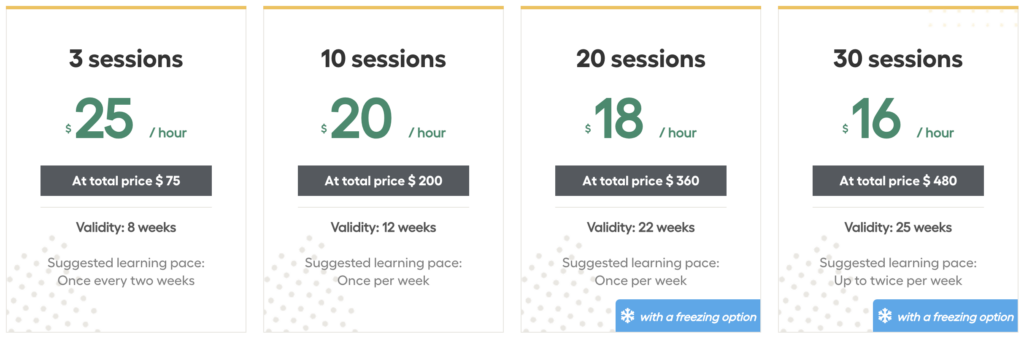

Harness the power of language with NaTakallam’s diverse services. Whether you’re interested in academic programs, 1-on-1 sessions, translation and interpretation, or Refugee Voices, explore our solutions and see how we can help you build a more inclusive and connected world.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Lenora Dsouza is an intern at NaTakallam and is currently pursuing her Masters degree in International Security at Sciences Po Paris. She is passionate about learning new cultures through travelling and language.

Language: A Critical Tool to Unlock Peace and Understanding Read More »