Director’s Notes of the Multilingual Beatbox Video

Contributor: Daniel Te, Summer Intern – Program Support Officer at NaTakallam

Two years ago, I beatboxed on the streets of Athens, Greece, on the last day of my study abroad program. During the performance, I felt some sort of connection towards the locals, as they challenged me to beatbox battles, shimmied along, and even gave me a smoothie. That’s when I knew there was more to discover about human connection at the intersection of music, language, and different cultures.

This past summer, during my internship at NaTakallam, I wanted to use the opportunity to tie in my passion for beatboxing together with the experiences of the language partners from displaced backgrounds at NaTakallam. This is where the project idea was born.

Universality and Distinctness in Language

Languages have many sounds in common. The “voiced bilabial stop” (another way of saying the letter “B” in English) can be found in a wide range of languages worldwide, and it is also the most fundamental sound for beatboxing. Practically any language has enough hard consonants to create a strong, basic beatboxing rhythm.

However, not only do different languages have sounds that are less common (such as خ, a sound in Arabic that is like a rough “K” vibrating at the back of the mouth or the Spanish letter J, “jota”), but even languages that do share many sounds can be pronounced quite differently. As a result, beatboxers that speak different languages produce rhythms that are structurally similar but aurally distinct.

In parallel, to a certain extent, the refugee narrative holds similar patterns. With over 80 million displaced persons worldwide (as of 2021), the journey of displacement is common among many people, but the character of their journey is shaped by their individual circumstances and the crises they flee. At NaTakallam, each language partner has their own unique story of displacement. This is what the Multilingual Beatbox video aims to portray.

The Process

The Multilingual Beatbox video combines each story of displacement into the general refugee narrative (universality), while highlighting a chosen word in their native language that represents their journey (distinctness). Each language partner introduces themselves by saying, “can you say [(word) in their native language]” to simulate a NaTakallam conversation session.

An early storyboard of the project.

After drafting a storyboard, I connected with various language partners, including translators and interpreters, on Slack (a communication channel for organizations). I aimed to gather a diverse group, reflective of NaTakallam multicultural team and language services in a wide range of languages.

Gathering a multilingual team for my beatboxing project (a “CP”, or “conversation partner”, is an internal term for language partners at NaTakallam).

It truly was a pleasure getting to know the language partners from all corners of the world. During the remote recording sessions, we had a great time and many of them got to meet some of their co-workers for the first time.

A meeting with Sayed, a Persian language tutor from Afghanistan based in Indonesia, and the fourth language partner featured in the video.

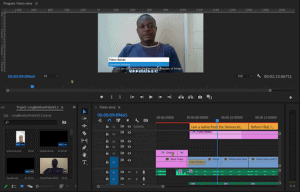

After the recording sessions, I looped the audio of each language partner saying their chosen word, editing it in the style of a beatbox rhythm. While it would have been exciting to have each of them do their own beatboxing, that would have been hard to coordinate remotely.

The video was produced in Adobe Premiere Pro, and the audio track was created in Adobe Audition.

Reflections on the Final Piece

This project hit close to home for me. My parents were refugees of the Cambodian Genocide in the 1970’s, so the journey of displacement was a recurring theme growing up. Throughout my life, I have been haunted by the question of what can we do in a world that still suffers constant refugee crises and how we can enable displaced persons to rebuild their lives. I have come to two conclusions.

One, open yourself up to the world. Embrace the universe. Beatboxing is my gateway, in that it helps me recognize what we have in common linguistically, as humans living in one world, and it only colors my vision more as I use it to engage with other cultures.

Two, enter others’ worlds and find the nuances. Engage in the issues that have persisted for displaced persons for decades and enable them in host communities. Speak their language and immerse yourself in the way they experience reality. With the Internet and services like NaTakallam or hausarbeit schreiben lassen (meaning “we speak” in Arabic and have word written in German ) , venturing into new linguistic worlds has never been easier.

To borrow the words chosen by the language tutors, it can be disheartening to hear that people around the world still face “discrimination” (“ubaguzi” – in Swahili) in their end of the “universe” (“l’univers” – in French), and experience “endless escaping” (“هروبٌ لا نهاية له“- in Arabic). The resolution of one refugee crisis doesn’t stop another from happening. Yet, seeing the Cambodian refugee community rebuild their lives in America, while still facing many struggles, gives me hope that displaced persons around the world have a genuine chance at “peace” (“صلح” – in Persian) and finding their new “earth” (“tierra” – in Spanish).

One day, I hope that “we speak” (or “we beatbox”!) as humans invested in each other’s well-being, compassionate of the struggles (universal and distinct) that people go through all around the world.